Subscribe to The Literary Fantasy Magazine 2026 for new fantasy stories every season.

Old Sorcery

Behold the strange tale of Persimmon the Great and his magically created duplicate, Tamarillo of the Bitter Seed. Callan has crafted an epic myth, rich with vigorous humor, striking commentary, and bitter irony.

SHORT FICTIONEPIC FANTASY

James Callan

3/15/202527 min read

About the Author:

James Callan is the author of the novels Anthophile (Alien Buddha Press, 2024) and A Transcendental Habit (Queer Space, 2023). His fiction has appeared in Apocalypse Confidential, BULL, Reckon Review, The Gateway Review, Mystery Tribune, and elsewhere. He lives on the Kāpiti Coast, Aotearoa New Zealand.

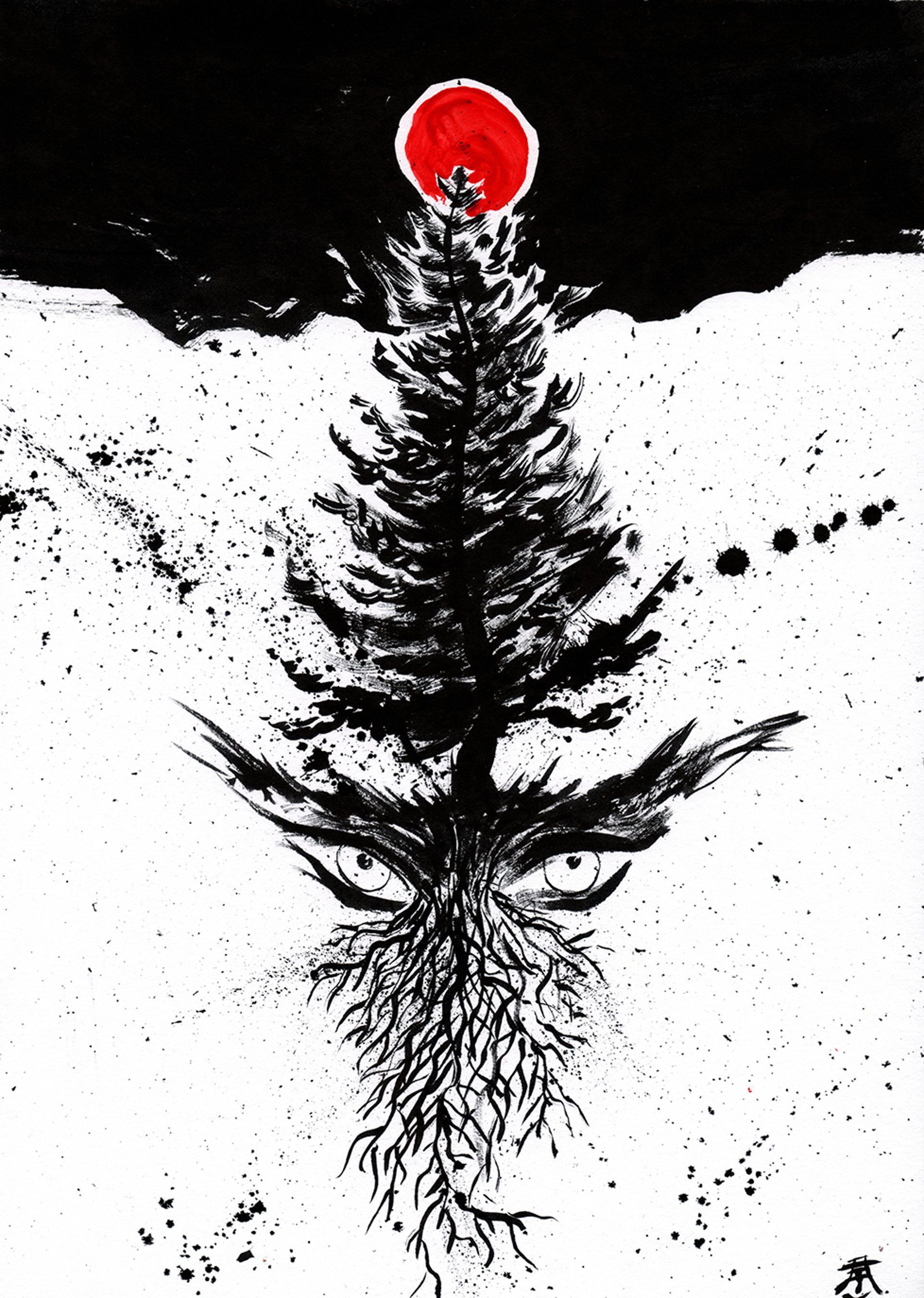

Artwork created by Kim Holm. More of James Callan's writing can be found in The Literary Fantasy Magazine: Winter 2025

In the days of yore, when the old, strong sorcery was more than myth, spells required blood, their potency strengthened by the lives put into them, their power amplified by the offering of souls. Magic made heroes of men, and many men, heroic or otherwise, met their deaths at the wrong end of magic. There were those born with the gift of wizardry, natural enchanters blessed with inherent talents. There were those, too, who passively benefited from trinkets imbued by the sorcery of others. It cannot be overlooked: there is a great divide between the man who launches fire from his fingertips and the man who brandishes flame with the aid of a wand, staff, or scroll.

Some men have aptitude for the sword, the plough, the pen. Others find their aptitude standing on the weathered planks of the prow, or sitting in the oiled saddle of a destrier. Many have little aptitude at all, paltry skills that can scarcely be dredged from the depths of their worthless shells. Fewer still, possess the rare aptitude for the arcana, the occult, the mysteries of magic. Some men—rarest of all—are born of magic, owing not their reputation to its potency, but to their very existence.

Some men stand out among their generation, among the many generations before them—the once-in-a-century mage who rises high, elevated to godlike status. Women, on occasion, rise as high as men—though the ways of the world work against them. It is often said and widely known to be true: behind every great man is a great woman. And while the hammer and the sword may favor the heavier build of man, magic holds no distinction, no discrimination in favor of the configuration of those who wield it. Yes, women have been known to rise as high as men, and one in particular, higher still, set the bar so far above the clouds to make any man, past or present, seem as small as an insect underfoot. One woman springs to mind, a dreadful sorceress who had no equal, who seized the world of Garden in her relentless grasp. But her tale comes later—much later—and her prodigious wrath is no way to start a story.

This story begins with men. Men powerful in magic, but so bereft of wisdom as to render their talents dubious at best—a double-edged sword held by the blade. Few men are truly powerful, and fewer men, besides, are wise with the power they do possess. Back in the days of yore, when the old, strong sorcery was more than myth, there was a man who used only what was required: blood, life, and many souls. He was a man of rare power, and he hatched the rarest man of all, a man who was born of magic.

* * *

Tamarillo of the Bitter Seed, a scion of his master, Persimmon the Great, grew from the rotten fruit of his predecessor’s garden. Persimmon had soaked the roots of the tamarillo tree in the blood of vermin he attracted with enchanted cheese. The rats, before they were sacrificed, grew to the size of toddlers. Charmed by the cheese luring them to their fates, the overlarge rodents walked to a nearby village like human children, laughing and playing among the locals. After weeks of visits and much play, cultivating bonds of friendship, the rats coaxed the human children to tag along for a special game of ring-around-the-tamarillo-tree. It was then all parties partook in their deaths, slain by Persimmon to feed the tree with their lifeblood, to germinate the Bitter Seed that would become his corrupted copy.

Tamarillo was born, not as an infant boy, but a full-bodied man. A natural adept, he learned magic from his master and excelled as if a long-toothed scholar of arcana. But he was Persimmon’s double, not his child, and he refused to obey the magician who created him. He took his own stances, pleasures, and passions. His study diverted from the paths Persimmon had laid out before him. Tamarillo was rebellious, naughty by nature. Inherently magical, his curiosity grew and soon he dabbled in dark arts and demoncraft. As was the wizardly custom of his time, he indulged in old sorcery, which was not old then, but remained undoubtedly cruel.

Within the first year of his conception, dozens of the nearby villagers came to Persimmon’s castle complaining of his tarnished offshoot, the perversion of Tamarillo, who they called not he, but it. “It stole my cattle.” “It cut off my cat’s tail.” “It comes in the night and seduces my wife.” “It took my daughter’s sacred virginity.” “It took my son’s.” “If we see it again, Persimmon, we are obliged to kill it.”

A stern look from Persimmon might have been enough to lay the villagers’ complaints to rest. For good measure, he transformed the boldest of speakers, a turnip farmer, into sea foam, which held its human shape for a half-second before it fell to the floor and seeped into the grotty cracks of ancient stone. But even as Persimmon was a malevolent bastard, so too was he fair. He bade the villagers stay to witness the summons of his grafted soul—his son, so to speak—whom the villagers called “it.”

“It,” Persimmon called Tamarillo, to chide his scion, but also to appease the fear-stricken villagers. “It shall no longer trouble you, or any people, on any lands beyond the grounds of this castle, the acreage contained by its outermost walls. It shall obey, because if it does not, it will suffer most horrifically by my hand.” Persimmon flashed a yellow grin through his white beard. “And it knows, just as you do, my good people, that my word is law. And the law… Well, it is unforgiving.”

“Now return to your hovels,” he dismissed the villagers, who left the castle with one less member to their numbers. “And you,” he glared at Tamarillo, who had been sulking while hidden behind the crowd. “Let it be known: life, mercy, kindness—what giveth may taketh away. You shall play nice, or I will unravel your soul just as I have weaved it into existence.”

Tamarillo bowed to his master, masking the venom within his heart with courtesy and smiles. He quieted for a year—well behaved, by all appearances—but his silence was a ruse, a nest for breeding the most despicable disobedience he could muster. Tamarillo was so devout to his disobedience to Persimmon that it became his religion. And he prayed, long and hard. He prayed, night and day.

After Tamarillo prayed for a year and a day to the demon known as Darkstain, after trading a quarter of his soul to invite the sinister prince into his heart, he used his newfound powers to taint the Clearwater River with hell-forged poisons and Hadean curses. Tamarillo’s actions led to the death of half a kingdom, spreading blight to the Endless Pasture and Emerald Fields, and the decay of the great mountain fortress, Castle Cloud.

These dire sins committed by Persimmon’s scion did not go unnoticed, though he remained ignorant to the demon living in the quarter-vacancy of Tamarillo’s soul, the dark menace making such vile acts of power possible. Had Persimmon known, he would have slain his son outright, sating the villagers’ requests for his death the year before. But awareness of demons aside, mercy gathers dust among the unpracticed tendencies of Persimmon the Great. In the end, he decided to banish his crude copy to a realm where time is a virtual standstill, where seconds stretch to eons, and ultimately, where Tamarillo would endure eternity, removed from mankind—a fate far worse than death.

But Tamarillo had foreseen his master’s plan. Driven by paranoia, moved by his mad intuition, he slit the throats of a thousand frogs and transferred their consciousness into the mind of a geriatric fruit bat. The bat, fueled by black magic and ten-hundred amphibian souls, became prophetic before burning out its newfound power and dying within the hour. In its limited time, the fruit bat scratched the words in dirt that divulged Persimmon’s intention to encapsulate Tamarillo in a sea glass stasis coffin. The enchanted coffin, with Tamarillo inside, would be dropped into the deepest trench of the deepest sea and sit there, unchanged, until the sun expired and the world withered into space dust.

With this knowledge of his otherwise intolerable fate, Tamarillo fled, traveling beyond the once-fertile fields he had reduced to ash, beyond the shadow of Castle Cloud’s ruinous husk, beyond the reach and influence of his former master and creator, Persimmon the Great.

* * *

Tamarillo fled to the gloomy haunts of the Greenwood, a forest spanning 900 miles in a crescent across the continent of Hyacinth. There, in the ancient woodland, he subsisted on mushrooms and moss, becoming deranged and skeletal, but otherwise at peace in his new, arboreal home. For years, among the trees, he led an ascetic life, abstaining from indulgences and avoiding all pleasures. Often, at night, dappled by the ivory moon, he would lay on the damp leaf litter gazing up to the silver-etched canopy and silently weep, deeply regretful for the terrible sins he enacted against the innocents of Clearwater Kingdom.

In the daytime, his sadness dissipated with the dew, and contentment came as commonly as the little brown mushrooms that sprouted after the rain. Peace was plentiful—rife to point of smothering—and serenity ate quietly away at Tamarillo’s rotten heart. The quarter demon in him poisoned everything he experienced, so the great wizard’s scion left the depths of the forest to seek absolution in suffering, hardship among the cold chaos of the Cloudy Mountain’s cave-pocked, goblin-plagued slopes.

Tammy, as he began calling himself, established his home near the treeline in the easternmost crags. There, among a copse of bristlecone pines, reputed to be several millennia old, he broke his do-gooders streak with the blood sacrifice of a sacred white stag.

No man shall fell the celestial white stag, for it is the holy animal of life. This, the shared decree of all kingdoms of Hyacinth.

No man shall take the life of the celestial white stag, lest he suffer death by the righteous wrath of God, by the King’s law and the headsman's axe. He who harms the sacred white fawn, the snow white doe, or God’s own alabaster stag, will undergo swift execution or slow torture, death by the means of the local lord’s whim. This, the Greenwood chapter in the Book of Hyacinth’s Common Laws.

Tammy summoned a bolt of icy magic from the cold depths of his black heart. It materialized between his fingertips, glowing radiant and cruel. He nocked the volatile bolt to a bow of fine yew and whispered incantations to guide its noxious malice into the breast of the albino hart. Drawing back, he took his aim, and released—Twang! It flew between the tall trees, behind boulders and shrubby obstructions, weaving to find its target, which fell dead upon the magic arrow’s impact over a mile from where it was shot.

The only downside to this spectacular technique was Tamarillo’s need to travel a mile to harvest his kill, and, even worse, a mile back the way he came with a mighty stag in tow. He sullied the sacred deer’s body by dragging its corpse by its hind legs, its antlers, even its ears, tarnishing its pristine pelt over the jagged rocks and twisted roots. Even after its molestation, the white hart was astonishing to behold; a regal beast of mighty pulchritude.

Tamarillo drained the creature of its blood, drawing out its soul with dire hymns sung only in Hell. He beseeched himself, “Tammy, please,” begging the darkest portion of his character, Darkstain within him, to awaken the trees with the rare life he had offered, the purest of souls he partitioned at their petrified stumps. The bristlecones trembled, uprooted themselves, and moved closer to the depraved man who had awakened them from a peaceful trance only a tree could ever know. They spoke slowly, not in audible words, but in groans and vibrations directly transmitted to the mind.

* * *

Tamarillo, with his band of bristlecones, terrorized the eastern ranges of the Cloudy Mountains, the Greenwood spreading northward from its great, granite roots. The humans of the mountain villages appreciated Tamarillo’s mass murdering of the cave goblins, who routinely raided the villagers. The humans did not, however, appreciate his mass murdering of them, which he did for no apparent reason, unless that reason was to satiate some sadistic hunger.

Northward, Tammy spread his infamy, warring with the wise forest trolls to collect their lives, yes, but more importantly, their horns, objects with potent magical properties needed to augment his devious witchcraft. Likewise, he victimized the human forest dwellers, pulverized by marauding bristlecone sentinels, or by the wild, indiscriminate carnage of Tamarillo himself.

Eventually, Tammy’s disreputable acts betrayed him, and his whereabouts were traced by his dastardly acts. A conspiracy of ravens blackened the sky above the Greenwood treeline, casting a shadow over the eastern slopes of the Cloudy Mountains. They witnessed the foul deeds of Tamarillo, the Bitter Seed, and flew westward to Persimmon's castle to inform the great wizard of the atrocities carried out by his pseudo-son.

Caw! Caw!

A wave of Persimmon’s gnarled fingers, and the carrion feeders’ discordant music transformed to decipherable speech: “The dark shadow that you birthed into this world has sullied the white stag’s soul. Hark! He murders men and trolls alike. And lo, he has awakened the oldest of trees and stripped them of their ancient wisdom, reducing them into mindless thugs, brainless cronies to act on his malevolent commands.”

Persimmon felt slighted, deeply insulted. “My own self!” He raged. “My own copy!” More than that, he felt responsible. “I planted the Bitter Seed. I nurtured my scion, bringing this wretched menace into the world. I laid a foundation to its roots, applied what wisdom I had, gave all of my craft of magic. I offered Tamarillo the world, and this is how he uses the gifts I have bestowed upon him?”

In a mindless conflagration of rage, Persimmon engulfed the ravens in flames. Cerulean fire, tinged with enhancement, danced on their black feathers, yet kept them alive, in constant torment.

Caw! Caw!

The dark-winged heralds screamed in agony, too bewildered by their pain to contemplate their confusion, unable to ask in resentment: Why, o merciless gods, do we burn, yet do not die?

Caw! Caw! Caw!

A wave of Persimmon’s spidery fingers, and the carrion feeders’ harrowing music translated to comprehensible accusations: “Why, great master, have you singed us with this unearthly blue flame? Why this betrayal when we bowed to your every whim?” It was all the birds could manage. Speech, magically enhanced or otherwise, became lost to them. Their bodies were on fire, and their minds were ablaze.

It was simply a case of killing the messenger—or, more specifically, not killing the messenger, but setting them afire with a magical flame that inflicted unbearable pain, but not death. Persimmon overreacted, unfairly and impulsively, but what is done is done, and he would make use of his blunder in what way he could.

“Go, ravens of fire! Set the sky aflame! Fly east, and burn the bristlecone pines to ash. Do this, and I will allow death to take you to a restful end. Take care of Tamarillo’s minions, and I will take care of the Bitter Seed himself.”

Desperate to expire, hoping to end their torment, the ravens cawed in furious delirium, flying east.

* * *

Tamarillo abandoned his diet of frugality, forgoing the consumption of mushrooms and moss. Giving up asceticism, he gorged on troll brains and human stew. He filled his belly on the slow-cooked bones of man and beast, and dulled his senses with hibiscus wine. He lay with the bristlecones, fornicating with them in strange ways, engaging in biologically futile pleasures. He killed needlessly, any animal or man that crossed his path. Darkstain, lodging in the darkest quarter of Tamarillo’s soul, was comfortable in his current host. Through countless misdeeds and depravities committed by Bitter Seed, the demon within him became satiated, and grew far stronger.

Full on troll flesh and human soup, the marrow of man and beast, Tammy slaked his thirst on hibiscus wine and made incomprehensible love to enchanted bristlecone sentinels. The bark was rough on his flesh, but he enchanted himself to endure the pain along with his pleasures. Heavy with food, dulled by wine, and busy in the engagements of his perversions, Tamarillo did not notice the eastern sky aglow with cerulean fire.

Too late, he heard the frantic cawing and torturous shrieking of the ravens dive-bombing his camp. The bristlecone sentinels swatted the sky, darkening their boughs with raven blood, but the blue flame of the birds set fire to the trees, reducing them to lifeless charred husks. Caught off guard, naked and exposed, Tamarillo was attacked at great disadvantage. The ravens’ offensive, however, was targeted at the ancient trees, and the young wizard managed to avoid any injury.

His bristlecones were lost, his army burned to cinders, his dendriform lovers slain. Tamarillo was devastated, and his counter strike was fierce. Through furious tears of frustration and grief, the Bitter Seed intoned to the demon within him, and Darkstain, obliging, ended the flaming ravens with a black belch of sulphurous plumes. The birds fell to the ground, cawing no longer, trailing black smoke and black feathers.

* * *

Not far behind his vanguard of flaming ravens, Persimmon flew east over the Greenwood canopy, carried by Nephele, a cloud nymph, magically bound to answer his summons. With fists full of her flowing, silver hair, and legs clamped tight around her slender waist, the old wizard rode the nymph at lightning speed while the trees blurred below with their furious aerial advance. Unbeknownst to their approach, the great threat looming nearer, Tamarillo brooded over the death of his bristlecone army, weeping on the side of the mountain. Unprepared and unaware, he sat defenseless, totally exposed.

Enchantment, however, has a way of coming back, igniting post-mortem even after its supposed expiration. Sorcery and luck are closely woven, the soothsayers preach, and luck, it would seem, favored the Bitter Seed in his most desperate hour. Resurrected by the faint residue of magic in its withered corpse, Tamarillo’s old prophetic fruit bat animated to unlife, activated by his master’s need. The fruit bat abandoned its sheath of papery skin, leaving its chiropteran husk and brittle bones behind, flapping into the night on ghost wings that carried it just ahead of Persimmon and his cloud nymph, Nephele.

It arrived luminous like the stars above. Little more than silver mist and white vapor, it whispered warnings on gentle gusts of cold, night air. Tammy, naked and pitiful among the scorched remains of the ancient bristlecones, heeded the words of the fruit bat spirit, its notification that Persimmon would arrive at any moment.

“Save your tears for another day, my lord, for you must prepare yourself—prepare yourself, quickly—for the sinister intention of your sire.” The fruit bat slowly vanished, dissipating on the chilled, mountain breeze. Fading from view, its fragile voice becoming fainter by the syllable, the bat’s final message warned his master of Persimmon’s old promise, the great wizard’s resolve to encase his tainted copy in a stasis coffin, to deposit Tamarillo into the deepest chasm of the widest ocean, or the core of the greatest mountain, or up and away to orbit the planet in the cold and vacuous nothingness of space.

The bat’s afterimage lingered, its message echoing in the bitter, silent night. Tamarillo looked west over the Greenwood, deciphered a silvery cloud approaching faster than any weather could carry it.

“Persimmon!” he spat his creator’s name as if uttering the foulest of curses. “You gave me life, yet you would not tolerate my individuality, my soul. You gave me life, yet all you ever wanted was a puppet, a golem to mimic your every aspect, to obey your every command.” Tamarillo ran to his hovel on the side of the mountain, donned his mage robes and his spell caster’s fingerless gloves.

“Persimmon, you fiend!” Tamarillo shouted to no one but himself. “The prowess of your magic is second to none. I have no doubts: I will die by your dire incantations before the moon crests the mountain. But hear this, you lank misfortune of a harpy’s miscarriage: though you may take me to hell with your magic, I will not fall to the fire without fighting tooth and nail, without spell and sword and righteous malice.”

He wrapped his wrists in pale silks and cloth of gold, enchanted fabrics plundered from the ancient tombs of goblin royalty. Their magical properties tingled against his skin, augmenting his power. He painted runes on his palms and across the center of his forehead, opening the channels of magic that surged within him. He donned a bronze circlet, a headpiece taken from a faerie prince, and as it rested on his brow, he felt its potency amplify his own inherent gifts. Lastly, he took the troll horns he had collected from his warring with the wise and magical folk of the Greenwood clans. He arranged them in a circle and stood in its center, praying to Darkstain, the demon who tainted his soul and had granted him great power. Crackling with magical energies, charged and ready to erupt, Tamarillo left his hovel and stood poised on the steep side of the mountain.

He could see it now, the close approach of a living cloud carrying Persimmon on its back. It descended, a nymph in cirrus skirts and a cumulus cloak, from high above the canopy of the Greenwood. The elemental spirit settled above the treeline, next to where the bristlecone husks lay charred and smoking. There, the great wizard who saddled Nephele dismounted to face his seething scion.

“Tamarillo,” the old man addressed his younger copy.

“Persimmon,” his mirrored, youthful version responded.

“You must know that my coming here before you is synonymous with your death.”

Tammy nodded. “I am aware you would try your best to make it so, yes.”

Persimmon laughed heartily, bitterly. “Trying and accomplishing are one in the same for a wizard of my power. There is not one without the other.”

“So it would seem, as well, with arrogance and ability, or old age and foul smell.”

“Or, in your case, my despicable, blighted duplicate: perversion and chaos, sadism and ruin.”

Tamarillo waved his hands in dismissal, prompted by his sheer annoyance and lack of patience. “Shall we commence with killing one another?”

“Let me answer your question with a question: are you prepared to die?”

Tamarillo spat back at his maker, his genetic facsimile. “Allow me to answer your question with a murderous incantation,” he replied, and without a single second to separate his last spoken syllable with the volatile magic he unleashed upon his opponent, the space between them filled with an arc of molten rock, spewed from the bowels beneath the mountain.

“Child’s play,” Persimmon mocked his would-be assassin, his child-turned-adversary. Before the lava could scorch his skin or singe his robes, the great wizard erected a luminous shield, flickering and sparking upon contact with the magma, stopping it short where it oozed to cool upon the ground.

“You guard yourself well,” Tammy admitted with a grin. “But what of your pet?”

“My pet?”

Too late did Persimmon reason that the cloud nymph, Nephele, was the “pet” in question. Too late to save her from Tamarillo’s secondary volley of lethal pyrotechnics. Before the old wizard could respond with a spell of his own, a defensive counter, Nephele was gauze on the wind, evaporated beyond any hope to coalesce ever again. Her scream was a high pitched gust of wind, loud at first, then ever so faint. Her piteous call may have trailed off for a while, but it was drowned out by Tamarillo’s laughter, which drew the irate attention of the most powerful wizard ever to walk the world of Garden.

“And now, you die.” So matter of fact were the words of Persimmon that one may have mistaken it for arrogance, an ego-driven bravado akin to the puffing out of one’s chest. But the ease with which he weaved his fingers to trace a golden rune of light, a radiant symbol that widened a portal to some distant, unearthly dimension, commanding a horned dragon, black as shimmering ink, to crawl forth from whatever hellish realm existed on the other side, bespoke of mastery beyond the need for chest-puffing machismo. This was no show of arrogance, but ascendancy. All at once, face to face with his death, Tamarillo understood the wide gap between his proficiency in magic and his creator’s near-divine supremacy.

“And now, I die,” Tammy echoed the words of his former master. The last image he saw in life was the wide maw of a monster from a bizarre, astral realm. Seconds later, many well-chewed, separate pieces of him travelled down the gullet of a dragon born across the cosmos. And that was that… Or so it seemed for the briefest of interludes.

* * *

Tamarillo had died, obliterated by his master, and yet part of him lived on. The dragon who had devoured him coiled into a tight knot of midnight, plated scales, twisting its serpentine body in on itself, groaning in agonizing discomfort—its meal, it seemed, was not to the monster’s liking. It belched acrid, black smoke and hacked up the blood and bones of Tamarillo’s devastated body. Among the ruined jigsaw of the scion wizard’s corpse, an apparition rose amid the disheveled gore and mutilated limbs. A small figure the size of a child, horned of head and hoofed of limb, laughed maniacally at the astral dragon’s plight, its obvious anguish as it writhed across the face of the mountain.

“What fresh corruption is this?” Persimmon faced the small, demonic figure. “What rancid devil rises from the belly of the dead?”

The child-size horror grinned to reveal sharp fangs and a forked tongue. “I am your own copy,” it declared. “Tamarillo of the Bitter Seed.”

“Nonsense!” Persimmon waved a hand in dismissal and disgust. “Do you take me for a fool? I can see quite plainly you are not my scion son, but a dismal creature from the netherworld.”

“I am Darkstain, son of Blemish, Lord of Rot, and child of Goreah, Queen of Anguish.”

“A demon of royalty,” Persimmon remarked with utter contempt as Darkstain bowed with exaggerated flourish. “You may have been born among the upper echelons of Hell, but even as a highborn prince, a demon is bound to their doomed and desolate realm. Tell me, foul creature, how have you come to this world, far too pure to harbor your blighted soul?”

“I am Darkstain, Prince of Misfortune, Lord of Decay, but I am also Tamarillo, who is your copy, and so I am also you, Persimmon the Exalted.”

“You speak in riddles,” Persimmon huffed. “Bad riddles, which make little sense. I will not stand here and tolerate games of guessing. Tell me plainly what you mean, and quickly, or hold your tongue and promptly prepare for your death.”

If Darkstain feared the great wizard’s power—his melange of spells that might undue the demon, fiber by fiber, flesh and soul—he betrayed no evidence of his anxiety. Instead, he laughed, how he had gained entry into the human realm, divulging his union with Tamarillo, the details of their contract that granted him haven under the pure, blue sky of Garden.

“He offered you his soul?” Persimmon’s disgust reached the depths of his core.

“One-quarter of his soul,” Darkstain declared. “Which is how, in a subtle way, Tamarillo still lives on. Inside of this stunted version of my netherworld whole, resides the fragmented ghost of your son.”

“Tamarillo is not, never was, my son.”

Darkstain spread his dwarfed limbs, his taloned fingers. “Semantics, old man. Though it cannot be denied, you two are very close—as close as can be. After all, Tamarillo is you, and you, him. Say what you will about your relationship, but you ought to know: you speak as a bitter father who has been estranged from his child.”

Persimmon scoffed. “My child, as you would have me call him, has abandoned his father, abandoned all reason, and finally, abandoned humanity. He has committed acts so heinous and cruel that he is more akin to a monster, like you, than a man, like me. And now what of my son? He is three-quarters dead, and the part of him that lives on dwells in the diminutive iteration of a vile wretch, a demon who has crawled out from its loathsome abyss.” He shook his head and waggled a bony finger. “Tamarillo has been dead to me since the day he murdered half a kingdom. I may have brought him into this world, but he is not my kin. He is no son of mine. He is all yours, Darkstain—and you are welcome to him.” Persimmon spat on the ground before him. “It is just as you say: Tamarillo is now a part of you.”

Darkstain chuckled, strangely deep for so small a figure. “It is what makes you, mighty Persimmon, a small part of me as well. I am Darkstain, Demon Prince of the netherrealm, but I am also Tamarillo, the quarter of his soul that gives me viability in this world, and by virtue of this, I am also you, a quarter-copy of the vintage mage who made me.”

Persimmon was troubled greatly by what he heard. He recalled the devastation and plague Tamarillo had inflicted on Clearwater Kingdom, the dark magic that now, in retrospect, resonated with demoncraft. So it was Darkstain, and not Tamarillo, who plunged into the chasm of doom, who took the great leap from misdemeanor to mass murder. Persimmon sighed, truly saddened. But one more look at Darkstain, who mocked him with gleeful, unrestrained giggling, and the wizard’s sorrow melted away, replaced by rage that simmered to boil over into hardened resolve—he would eradicate Darkstain from existence.

“You do not belong in this plane of reality. Yours is another realm.” Magical energies—luminous hues of blue, white, and gold—coalesced to swirl around Persimmon; the residue of raw power agitated his loose robes and long, white beard. “You have no place in this world,” he condemned the apparition before him, “and I will not tolerate your presence here for another minute.” He glared at the quarter-sized demon, the quarter-soul of his scion, thoroughly corrupted by evil-incarcerate. “But neither will you return from whence you came. Never again will you walk the green lands of Garden, or return to your throne of corpses in the gloomy caverns of the shadow realm.”

“But enough talk.” And without a further word, quick and blinding as lightning, Persimmon traced a series of intricate runes in searing, white light. The symbols hovered in the air before him, growing in luminosity and size.

Darkstain’s impertinent laughter and insolent smirk vanished amidst the foreboding, bright light. He cowered in its glare and, shielding his serpent-slitted eyes, quickly inscribed his own dark sigil, to erect an adequate shield against his impending demise.

Blood, lives, and souls—the requirements for the strongest of magic. With enough blood on his hands to last an eternity, Darkstain summoned a shield of defense forged on the countless lives he had taken, the innumerable souls he had spoiled. Persimmon, who was stronger than the enemy he wished to thwart, had, nonetheless, failed to account for the presence of a demon prince. He had prepared for Tamarillo, an encounter requiring the blood, life, and soul he had applied for the occasion. At this point, Persimmon was tapping from a dry spring.

Still, this was Persimmon, a wizard famed for being the strongest to ever walk among the world of Garden. If he was unprepared, what of it? He would make do, and expeditiously slay the demon before him. And so he raised his gnarled, old hands and unleashed the magical force he willed into reality. A beam of pure, astral energies borrowed from celestial bodies occupying distant solar systems erupted from Persimmon's withered palms. It hit Darkstain, colliding with the Hellfire shield planted before him in defense, and sent the demon hurtling across the slopes of the cloudy mountains.

And still, Darkstain endured. He rose up from his knees, holding the ragged ruins of his shield, and approached Persimmon for another round of violence. His grin returned to spread across the demon’s face, for he determined that the old wizard was spent and unprepared. Darkstain was weak and injured, but no longer saw himself as outmatched. Beneath the layers of his own, demonic spirit, he felt the soul of Tamarillo—what was left of it—imprisoned within him, crying out from the realms between. Sadistic to the end, his old host’s plight lent the demon newfound strength.

“Shall we make an end to this?” Darkstain asked Persimmon when he crossed the rocky slopes to face his adversary yet again.

“It is I who shall make an end of you,” Persimmon answered, and although his words carried ferocity, his retort came with a sputtering of blood. He hobbled, cradling his torso as if an arrow had pierced his guts. “Though it would seem,” he laughed in a blend of amusement and bitterness, “that this might, indeed, be my end as well.”

As before, he sighed in sadness, but smiled, too, as he traced more runes, sent forth more blinding light on beams of magical energy. It was the final thread to the tapestry of his vast power, the last drop among his reservoir of potency. Without the blood, the lives, the souls to fuel his summons, he took of himself—Persimmon, a depleted husk, teetered on the brink of death. Had he killed Darkstain? He was not entirely sure.

Knowing his seconds scarce, he targeted his heart while it still beat in his chest, drawing out the last life that remained to it, crafting a spell of utter destruction. Persimmon scanned the mountainside for Darkstain, the blight he would obliterate from the purity of Garden. But the demon was nowhere in sight, and without a target for the use of his spell, nor a single minute of breath remaining to him, Persimmon stored his dire magic in the stasis coffin he had intended to use to imprison Tamarillo.

Tamarillo… it was of his scion that Persimmon’s final thoughts lingered on. My dear boy… Oh, how I failed you. With the cataclysmic spell inside, Persimmon sealed the stasis coffin, fell to the rocks at his feet, and expired on the slope of the mountain.

* * *

In the chaos amidst the penultimate moments of Persimmon’s battle with Darkstain, the weakened demon escaped the wizard’s final spell, which surely would have marked his end. Drawing from the powers of Tamarillo, who shared his existence, and augmented by the untold barrels of blood, the countless souls his cruelty had amassed, Darkstain cast a spell to transfer his soul, abandoning his body which swayed on the edge of expiration. He did not have time to be choosy, his luxury of choice limited to the first living thing that he saw. And so, Darkstain shifted his spirit into the nearest creature, a woodlouse, with aims to recover his vigor.

The transfer of souls was a temporary measure, one that would last no longer than needed. This was, in any case, the intended plan. But intention and plans are fickle things in any world, more so still in a land of magic and demons. Fate, as it were, served its own intention. And fate, as it often is, was a cruel, sadistic bastard.

The woodlouse, who was a demon prince, and the host to a distant part of Tamarillo, too, settled on the bark of a tree of no special significance, a run-of-the-mill conifer. But luck and fate and magic are kin to chaos, and luck and fate would have it that magic once scathed that particular, not-so-particular tree. A deep gash in one of its lower, larger boughs glistened with liquid amber, and the woodlouse, beneath its flow, was encased in the dark resin bleeding freely from the wounded tree. The insect version of Darkstain, and the residual soul of Tammy inside, struggled against the sticky substance as it coated its legs, abdomen, thorax, and eventually, its head. But here was a battle that was truly futile, and the insect-demon-wizard-soul was entombed, buried alive.

Outside of the small, contained space of the stasis coffin nearby, the rest of the world carried on. All across the lands of Garden, from the Greenwood to the Cloudy Mountains, from the once-blighted Emerald Field to the recovered Endless Pasture of Hyacinth, and beyond, to the continents that spread east—Dahlia, Zinnia, and Dianthus—time behaved as it always did, passing in a series of nights and days that aged people, all living beings, and all objects, items, and places, a constant continuum of movement, change, and decay. The sun rose, crested the sky, lowered beyond the horizon; the moon mimicked her partner’s steps. Day, then night. Day, then night. Repeat. Ten thousand days and ten thousand nights—this, only the beginning. Seasons came and went. Epochs and eons fell away like autumn leaves. One million years. Two, three. Tree resin hardened to amber, and a woodlouse was preserved inside, a demon’s quarter-soul nestled in its arthropodal husk.

One day, when the sun rose to bathe the world in light, just as it always does, a passing traveler chanced upon a ring of petrified bristlecone trees. It was a curious sight, and diverted the man from his purposes. A trapper who wished to test the eastern slopes of the Cloudy Mountains, its treeline where certain mustelids of snow-white coats were reputed to dwell in healthy numbers; the man was drawn to this spot, but set down his trapping gear when he came upon a strange box glowing at the edges of its sealed lid. The rising sun poked its brilliant crown above the towering mountains and, as if a sign from the gods above, or the guiding hand of fate, its magnificent pillar of light shone to spotlight the smooth, sea-glass casket that radiated aquamarine. As the trapper approached the strange, spectacular coffin, the great shafts of sunlight shifted over and behind his shoulder, whereupon they set aglow an impressive chunk of raw amber, settled among the rocks.

A pure white pelt of a wolverine, a martin, a weasel or a stoat—these are fine things. But one does not idly walk past abandoned treasures sitting unattended in the heart of the wild. One cannot ignore an ornate chest aglow from within—not even a trapper who has mustelids on his mind. And so, the man approached the sealed coffin, oblivious to the power and history locked within its moss-strewn glass.

Using the sturdy branch, which served as his walking stick, the traveler wedged a hardwood staff between the lid and casket, working hard to pry open its seal. After some struggle, the lid came loose, but not gently. The power contained within, suddenly set free, exploded upward as if the volatile eruption of a volcanic blast. The heavy glass lid flew high above the canopy of the Greenwood. It sailed through the air in wild circles, scraping the clouds, and crashed a mile or more down the slope of the mountain. The trapper was blinded by the power of the spell. But he did not dwell on this sudden impairment—quite frankly, he had not the time. Seconds after he lost his sight, the trapper was reduced to boiling blood and flaming innards, incinerated to ash and dust.

The spell, which seemed to be sentient with a clear purpose, shifted east, then west, up and down the slope of the mountain. It resembled an angel in flight, but shapeless—a blob, a jellylike creature, made of raw power and light. It weaved through the ring of petrified bristlecone stumps, then suddenly paused, grew brighter, larger, and approached a sizable chunk of amber laying exposed beneath its terrible glow.

The spell, which was sentient, was the last trace of Persimmon’s soul, extracted from his living heart a million or more years prior to that moment. Since its conception, the magic stewed in the passing millennia, the indeterminate eons, experiencing no time at all, but waiting, nonetheless, for this fateful moment. It condensed in on itself, concentrated energy packed into the size of a mustelid’s beady eye. It shot forth, a dreadful bullet, into the heart of the amber stone that housed an ancient woodlouse within.

Crack!

The amber split into four jagged pieces, shards of stone the color of marmalade. They smoked upon the rock where they had been scattered, trembling with energy, each with its own quarter of woodlouse corpse within. The last phase of the spell took effect, lifting the hot, smoking shards high into the air and dispersing them, each one, into various directions across the vast lands of Garden.

Four shards, one for each continent, distributed across the wide-ranging world. Each fragment was placed, not randomly, but with forethought and purpose, planted in unattainable locations—deep caverns, high mountain spires, the ruins of a haunted, wasted kingdom, and the bottom of a deep, cold lake. To the west, in Hyacinth, and the south, in Dahlia; to the east in Zinnia, and the cold, arctic north of Dianthus; the amber shards settled in their new and implausible places. There, they would rest, perhaps for another million years, for untold millennia, undisturbed through quiet eons.

Or perhaps they would be found. But by who? Legends of the future. Myths in the making. More names, more history, more steps in the never-ending dance of time.

And thus ends the story of Persimmon, the exalted mage, and his scion, Tamarillo of the Bitter Seed, marking the termination of their feud, their misdeeds, their various triumphs, crimes, and perversions. Here is the juncture in time that concludes the story of Darkstain, the demon prince, and the creation of the amber shards, the adventures and calamities that their power would later influence.

But stories, like time (barring stasis coffins), never truly end. They flow and continue, endless, ever shifting, developing, growing. For some, this is the end of the story. But at the end of every story is the beginning of another…

Art by Kim Holm

Logo by Anastasia Bereznikova

Contact: editors@thearcanist.net | business@thearcanist.net

Copyright © 2025 The Arcanist: Fantasy Publishing, LLC

ISSN: 3069-5163 (Print) 3069-518X (Online)